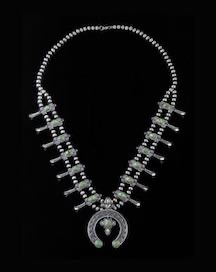

From ancient bone amulets to finely crafted squash blossom necklaces so coveted that they are imitated around the world, the history of Native American jewelry is a story of cultural resilience.

Archeologists have found evidence of Native American jewelry dating back to the Paleo period of 10,000 BC. For centuries the native people in America used the materials at hand, primarily shell, stone, bone, and other natural materials. European explorers introduced beads and metalwork in 16th Century. Native Americans acquired beads through trade and quickly incorporated them into their jewelry, clothing and accessories. It would be few hundred more years before they practiced silversmithing.

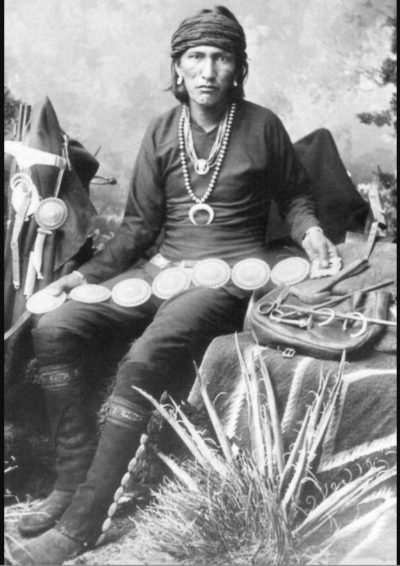

The art of silversmithing is relatively new to Native American tribes. It wasn’t until around the 1870s that the first tribesman, Atsidi Sani, a Navajo, learned silversmithing from a Mexican silversmith. (See top photo)

Early Native American silversmiths often made their jewelry from coins. They melted American coins until the U.S. government prohibited the defacement of currency. Then they switched to using Mexican coins. Pieces were bold and heavy incorporating locally mined turquoise and other stones and shells artists might trade for. The designs were influenced by their spirituality as well as their invaders. (The Naja of squash blossom necklaces comes from the symbol often worn on Spanish explorers’ horses.)

Silver jewelry was not only an adornment of Native Americans, it was their savings account. A heavy silver turquoise cuff could be traded for supplies or food.

Wild West Souvenirs

In the history of Native American jewelry, the commercial era didn’t take off until the turn of the 20th Century when railroad transportation opened up the Southwest to tourists. The jewelry styles changed to suit the desires of tourists who preferred more delicate pieces with “Indian looking” designs such as arrows, feathers, thunderbirds.

Those early days are often referred to the Fred Harvey era even though a lot of the jewelry sold in Harvey’s gift shops wasn’t entirely made by Native Americans, if at all. That’s a whole other story. But in short, the early success of a few Native American artists and the non-Native Americans who imitated them, encouraged the passage of the Indian Arts and Craft Act of 1935.

Indian Arts & Crafts Act

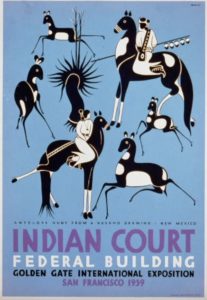

The Act, a part of U.S. Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, sought both to encourage Native Americans to sell arts and crafts and to discourage others from counterfeiting their work. It created the Indian Arts & Craft Board which showcased Native American goods everywhere from the Golden Gate International Exposition to the Paris World’s Fair.

The law also made it a federal crime to intentionally label jewelry and art as Native American-made when it is not. Although, the punishments were not huge – Maximum $2,000 fine and no more than six months in jail. Proving intent was also not easy.

The marketing aspect of the Act was successful. Sales of Native American arts immediately grew and enabled some tribal members to become self-sufficient. The primary jewelry making tribes include: the Navajo, Zuni, Hopi and the Pueblo Indians.

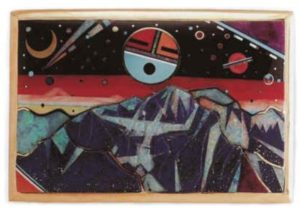

By the 1950s, second and third generations of Native American jewelry artists were selling their craft. Some began to experiment with different styles, materials and techniques. Artists such as Charles Loloma and Preston Monongye ushered in a new contemporary look to tufa cast jewelry. The lines between Navajo, Zuni, Hopi and Pueblo styles began to blur as Native artists borrowed designs and techniques previously unique to other tribes.

Imposters Continue

Perhaps, not surprisingly the Act of 1935 was less successful at discouraging unscrupulous sellers of imitation goods. By the 1970s Native American jewelry was at a peak. Artists were selling squash blossom necklaces as fast as they could make them. But as is the case when any product becomes hot, the number of counterfeits exploded. Loads of Native American-style jewelry was produced in Mexico and other countries, and is still passed off as Native American-made.

By 1990, the U.S. Congress was compelled to strengthen the original act. Native American arts had become a billion-dollar industry. Violators of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 can face a fine of up to $250,000 or a 5-year prison term, or both. Business violators can face up to a $1,000,000 fine. Also, no longer would prosecutors have to prove the seller intentionally sold imitation goods, putting the onus on resellers to verify authenticity of the items they sold.

Even still, it wasn’t until 2012 that federal law enforcement cracked down. They arrested a New Mexico shop owner and his supplier for importing and selling thousands of counterfeit Navajo and Zuni jewelry pieces that were made in the Philippines. Pieces were even signed with a Native American-sounding name, an artist authorities discovered did not exist. Authorities seized more than 350,000 pieces in the raid and estimate that the shop owner had already sold thousands of fraudulent pieces over the decade prior to his arrest.

Since then authorities have arrested more people for violating the Act, including a Texas man who sold imitation goods on Ebay in 2019. Meanwhile, according to the Economic Policy Institute, more than 25% of Native Americans and Alaskans still live below the poverty line.

New Old Style

Now with commercial sales of Native American jewelry well into its second century, third and fourth generation artisans continue to honor their heritage in their designs. Neo-traditional pieces hold onto to some of the most iconic design elements of early American jewelry while incorporating a modern flair. Here are just a few of the contemporary Native American artists keeping the culture alive.

For more on the history of Native American jewelry, check out these books:

- Dennis June’s “Fred Harvey Jewelry: 1900 – 1955”

- Pat and Kim Messier’s “Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry: Artists, Traders, Guilds, and the Government“

- Last, but certainly not least, Dr. Gregory Schaaf’s wonderful encyclopedic collection: “American Indian Jewelry I: 1,200 Artist Biographies,” “American Indian Jewelry II: A-L 1,800 Artist Biographies,” and “American Indian Jewelry III: M-Z 2,100 Artist Biographies”